История рода Фон Мекк

Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Research Inc.

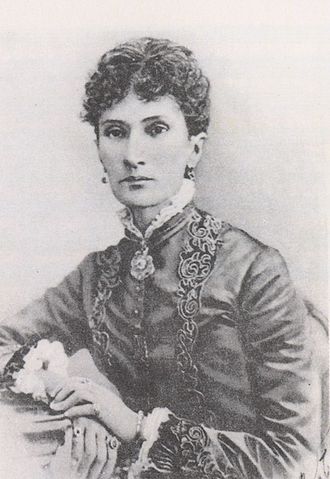

von Meck, Nadezhda (1831–1894)

Wealthy Russian patron of music who supported one of her country's greatest composers during a critical period in his career, maintaining years of correspondence that provide valuable insights into the daily life and creative mind of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Name variations: Naddezhda, Nadeja, or Nadejda von Meck; Madame von Meck. Born Nadezhda Philaretovna Frolovskaya (also seen as Frolowskaya) (Надежда Филаретовна Фраловская) in Znamenskoye, near Smolensk, Russia, on February 10, 1831; died on January 13, 1894, in Wiesbaden, Germany[MISTAKE!]; father was an avid amateur violist; married Karl Fyodorovich von Meck (an engineer), in 1847; children: 18, of whom 11 survived.

Married at 16, encouraged her husband to leave the work he despised as a bureaucrat to strike out as a railroad entrepreneur; widowed, after her husband had garnered an enormous fortune, by his sudden death at age 46; turned to music, commissioning pieces from the young composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, who entreated his patron for a subsidy that would allow him to devote himself entirely to composing; began an intense 14-year correspondence with Tchaikovsky (1876); ended the relationship suddenly for reasons unknown (1890); death of Tchaikovsky followed by hers, only two months later (1894).

Patronage has long been central to art. The Greek Acropolis, the Sistine Chapel, and the operas of Mozart are all works created as a result of support from individuals or governments. One of the most famous examples of private patronage in history was that provided by the wealthy Nadezhda von Meck to the Russian composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, to whom she gave extraordinary moral and financial support for 14 years while he was establishing his reputation. The great legacy of Nadezhda von Meck includes not only the beautiful music of one of the world's best-known composers, but the lengthy correspondence that documents the unique friendship of this patron and artist and opens a window onto the creative workings of Tchaikovsky's mind.

Nadezhda Frolovskaya was born on February 10, 1831, near the Russian city of Smolensk, west of Moscow. Her youth was typical of an upper-class girl growing up in imperial Russia at that time, except for the intensity of her love for music and skill at the piano, cultivated by her father, who was a keen amateur violinist. Just before her 17th birthday, Nadezhda married Karl Fyodorovich von Meck, a 28-year-old engineer employed as a bureaucrat by the Moscow-Warsaw railway. Nadezhda soon gave birth to the first of 18 children, 11 of whom survived.

Karl's earnings were modest, and in the first years of marriage, life for the couple was hard. "I had to be wet-nurse, nanny, servant, tutor, and seamstress to all my children, and my husband's valet, book-keeper, secretary and aide," wrote von Meck. Such duties were unusual in the life of an upper-class woman. Nadezhda urged him to strike out on a new career. "In the civil service," she later wrote, "a man must forget he has a reason, will, human dignity—he is just a puppet, an automaton. I was unable to stand it, and begged my husband to resign…. When he did, we found ourselves in such straits that all we had was some twenty kopecks per day."

But the period of hardship was to pay off. During the 1860s, railways were being built throughout imperial Russia. At Nadezhda's urging, Karl found a financial backer and became a builder of railways. He quickly amassed a huge fortune, and the couple began to enjoy a life of luxury, moving between their sumptuous townhouses and large estates. The business acumen and foresight von Meck showed in encouraging her husband into entrepreneurship was rarely to fail her.

A beautiful, passionate woman, Nadezhda grew restless in her marriage and became involved with her husband's young secretary, Aleksandr Iolshin. While Karl remained unaware of the affair, their older children knew that their youngest sister, Liudmila , known as "Milochka," had a different father. When Milochka was four years old, one of the children revealed Nadezhda's transgression to Karl, and family legend has it that in response he suffered the fatal heart attack that killed him at age 46.

Left a wealthy widow, Nadezhda von Meck was nevertheless unprepared for her husband's untimely death. She became a recluse, and except for doting on her children, showed little interest in anything except music. She already employed a cellist to accompany her at playing the piano, and she soon hired a violinist, Iosif Kotek, to live with the family. Music was a commonplace and relatively inexpensive form of home entertainment for the wealthy. It was not unusual, in this preelectronic era, for Russians to hire musicians and composers to provide occasional music in their households. Kotek, a former pupil of Tchaikovsky, adored his teacher's music. It was he who suggested that von Meck commission Tchaikovsky to compose pieces especially written for piano and violin. Tchaikovsky agreed, and in late 1876 he and von Meck began to correspond.

You are the only person in the world from whom I am not ashamed to ask for money. In the first place, you are very kind and generous; secondly, you are wealthy. I should like to place all my debts in the hands of a single magnanimous creditor by whom I should be freed from the clutches of moneylenders.

—Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky to Nadezhda von Meck

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky had been born into a family that had served Russia's tsars for several generations, mostly as army officers. His uncle and namesake had fought against Napoleon's troops when they invaded Russia in 1812. His father Ilya, a mining engineer of prominence in the mining town of Votkinsk, had many serfs and a hundred cossacks at his disposal. As an important civil servant, the elder Tchaikovsky could provide for his large family, and he married three times, losing his first two wives to illness and death. Tchaikovsky's mother Alexandra gave birth to six children, adding to the two by the first marriage. Tchaikovsky was 14 when his mother died, and he mourned her passing all his life. His father's third wife had no children, but Peter maintained lifelong attachments to all his siblings.

Tchaikovsky showed an early interest in music and began to study the piano at a young age. When his father retired and moved the family to St. Petersburg, Tchaikovsky obtained a law degree and a position at the Ministry of Justice. He was handsome and charming and created a brilliant social life on the fringe of high society, but he was dissatisfied with the practice of law. When he resigned from the ministry to devote himself entirely to music, he imposed an economic hardship on a family fortune that had never been large. At first he earned money giving piano lessons and accompanying singers. At age 26, he became a professor of harmony at the Moscow Conservatoire, where he composed his first three symphonies, his first Piano Concerto, three operas, the tone poem Romeo and Juliet, and the ballet Swan Lake. He was on the brink of fame but still struggling economically when Iosif Kotek contacted him about writing music for Nadezhda von Meck.

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky was high strung and intense, a complex person whose moods lapsed at times into depression. He has been described as "over-sensitive, over-shy, weak of will and overwhelmingly, frighteningly strong of emotion," and it was not unusual for him to avoid concert halls where his music was being performed, or to shun his family and friends. Seeming at times to flee human society, he could also be attractive and charming, and was greatly loved by those who knew him. The composer Rimsky-Korsakov described Tchaikovsky as "sympathetic and pleasing to talk to, one who knew how to be simple of manner and always speak with evident sincerity and heartiness. A man of the world in the best sense of the word, always animating the company he was in." The loss of his mother, inborn emotional complexity, and creative genius explain much about the character of Tchaikovsky, but his homosexuality also accounts for some aspects of his personality. Living in morbid fear of discovery, he eventually went so far as to marry to disguise his sexual persuasion.

In late 1876, the 36-year-old Tchaikovsky was delighted to obtain a commission from the 45-year-old widow, but he remained in dire financial straits nonetheless. It was Nikolai Rubinstein, virtuoso pianist and Tchaikovsky's superior at the Moscow Conservatory, who suggested to the young composer that he apply to his new mentor for a loan. After von Meck wrote that she would like to know the composer better, their relationship blossomed through a correspondence which grew voluminously into hundreds of letters written over a 14-year period.

From the outset, however, it was a basic tenet of this remarkable friendship that von Meck and Tchaikovsky would never meet. Still a recluse at this stage, von Meck may have feared repeating the physical relationship which might have resulted in her widowhood. In any case, she wrote to the composer, "the more fascinated I am by you, the more I fear acquaintance." Tchaikovsky, shy as he was, and fearful his homosexuality might be discovered, was more than happy to honor her request. Although the two lived near each other at times, and occasionally saw each other at a distance, they met only twice, and then by accident.

Von Meck quickly assumed a central role in Tchaikovsky's emotional and professional life. In 1877, the year after their correspondence began, the composer wrote that he had decided to marry Antonina Ivanovna Milyukova , who was a virtual stranger to him. He perhaps hoped that Milyukova would look after his needs, but the marriage proved from the outset to be a disaster. Writing to von Meck, Tchaikovsky never describes his problems with a physical union but dwells on the incompatibility existing between bride and groom. Von Meck, who wrote of her great reservations about the marriage, also offered him what epistolary support she could during the months when the relationship was dissolving. By the end of the first year, the intensity of both correspondents had made the composer and his patron emotionally dependent on one another. But when Madame von Meck suggested that they should assume the intimate form of address with one another, Tchaikovsky declined to do so.

Nevertheless, the relationship assumed a more intimate dynamic. After von Meck asked for photographs not only of Tchaikovsky but other members of his family, large numbers of pictures were exchanged. Their letters were also filled with comments about political events, gossip, family events, and personal observations. The two were compatible as conservative Russians devoted to the tsar and the Orthodox Church during a period when the imperial system was under attack from radicals. Music, of course, was also an important topic. Von Meck did not like Mozart's music, for example, while Tchaikovsky adored it. He endeavored to change her musical taste, and wrote about his works in progress, explaining sections as they were composed. A great deal of what is known about his composition of Eugene Onegin and the Fourth Symphony comes from their correspondence, and his Fourth Symphony was dedicated to von Meck, his "beloved friend."

Von Meck's support began as occasional subsidies, and gradually increased until she was sending Tchaikovsky a generous monthly stipend amounting to more money in two months than he had made teaching at the Moscow Conservatory in a year. When he eventually decided to resign his post to devote himself to composing full time, the decision met with von Meck's full support. Her generous patronage allowed not only new creative freedom but a chance for the composer to travel abroad. She also made her estates, including the magnificent Brailov, available for him to visit often for relaxation.

Tchaikovsky was never a prudent money manager, and it was not unusual for him to give away large amounts of the money von Meck bestowed upon him. When his funds were low, she sent more or doubled his monthly allowance. This extraordinary generosity and moral support continued until the composer was professionally well established and financially secure.

How and why the end of this unique relationship came about is not clear. At the time, she wrote to him that financial catastrophe meant her subsidies must be discontinued, and although it is true that her family suffered a temporary setback, railroads were soon booming again. Other members of von Meck's family wrote to the composer that her health had deteriorated, making it impossible for her to continue writing, and Tchaikovsky probably feared that she had been put off by learning of his homosexuality. This may even have been true, because stories about his liaisons circulated continuously. More probably, however, von Meck's many living children resented their mother's financial output, especialiy

after his compositions had begun to earn him a great deal of money. Whatever the reason, Tchaikovsky bitterly resented the end of this friendship, and it is said that her name was on his lips when he died of typhoid three years later, at age 53. Von Meck died two months later.

Tchaikovsky, in a sense, was the wealthy patron's dream. Without her support of him, Nadezhda von Meck would have been just another wealthy Russian widow. With it, he produced some of his greatest compositions, including such major works as the Sleeping Beauty ballet, his Fifth and Sixth symphonies, Hamlet, and Eugene Onegin. Von Meck, in turn, was the artist's dream—a non-judgmental figure, and a haven, perhaps even the mother that he always missed. Tchaikovsky wrote her, "I have never in my life encountered another soul as kindred and close to me as yours, responding so sensitively to my every thought, my every heartbreak." And for posterity, there is not only the music but the mind of the musician, revealed through his moods, his attitudes, and his intimate views on his own compositions throughout the hundreds of letters he wrote to his patron.

sources:

Bennigsen, Olga. "A Bizarre Friendship: Tchaikovsky and Mme von Meck," in The Musical Quarterly. Vol. 22, no. 4. October 1936, pp. 420–429.

——. "More Tchaikovsky von Meck Correspondence," in The Musical Quarterly. Vol. XXIV, no. 2. April 1938, pp. 129–146.

Bowen, Catherine Drinker and Barbara von Meck. "Beloved Friend": The Story of Tchaikowsky and Nadejda von Meck. NY: Random House, 1937.

Brown, David. Tchaikovsky: A Biographical and Critical Study. Vol. I. NY: W.W. Norton, 1981.

——. Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years 1874–1878. Vol. II. NY: W.W. Norton, 1983.

——. Tchaikovsky: The Final Years 1885–1893. Vol. IV. NY: W.W. Norton, 1993.

——. Tchaikovsky: The Years of Wandering 1878–1885. Vol. III. NY: W.W. Norton, 1986.

Craft, Robert. "Love in a Cold Climate," in The New York Review of Books. Vol. 40, no. 19. November 18, 1993, pp. 37–41.

Garden, Edward, and Nigel Gotteri, eds. "To my best friend": Correspondence between Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck 1876–1878. Trans. by Galina von Meck. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993.

Griffiths, Paul. "Perfect Partners: The romantic dialogue of a melancholy composer and a passionate lady," in The Times [London] Literary Supplement. No. 4705. June 4, 1993, p. 18.

Tchaikovsky, Piotr Ilyich. Letters to his Family: An Autobiography. Trans. by Galina von Meck. NY: Stein and Day, 1981.

Volkoff, Vladimir. Tchaikovsky. A Self-Portrait. London: Robert Hale, 1975.

JohnHaag , Associate Professor, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia